[06.02.24] Discover our key policy findings in policy fiches and summary graphics!

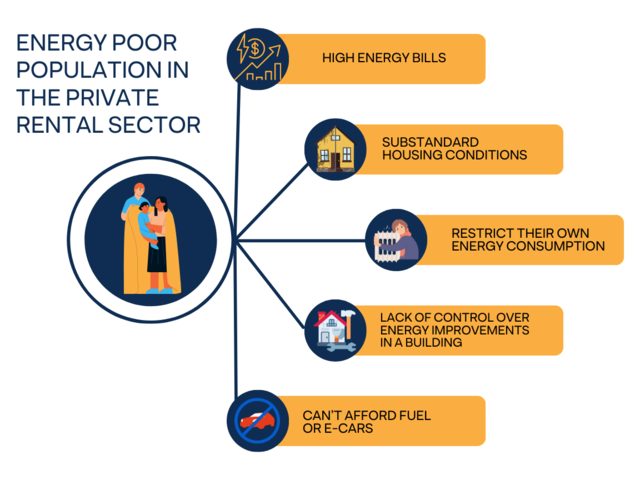

At the core of ENPOR’s recommendations is the need for EU Member States to establish a robust framework for diagnosing and monitoring energy poverty as addressed by the EU Commission. The ENPOR research findings emphasize the importance of combined policy measures that include comprehensive policy approaches that should focus on better landlord targeting, pushing for higher energy efficiency of buildings combined with information and training measures, fostering a sense of responsibility in neighborhoods, and improving local framework conditions. Energy poverty is a pressing concern in the Private Rented Sector (PRS) in the EU. Low-income, high-energy costs and poor or inadequate housing conditions, lack of control over energy improvements in a building, regulatory gaps and affordability issues disproportionately affect vulnerable populations, leading to increased social inequality and health disparities.

ENPOR’s policy recommendations address energy poverty in the PRS, emphasizing the importance of access to affordable and appropriate energy efficiency improvements, tenant empowerment, and regulatory measures.

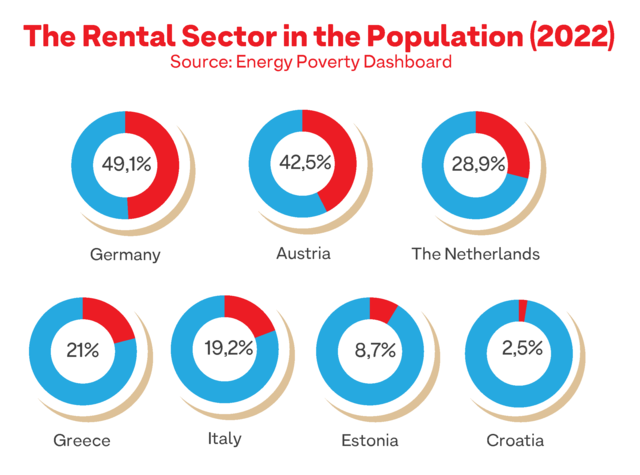

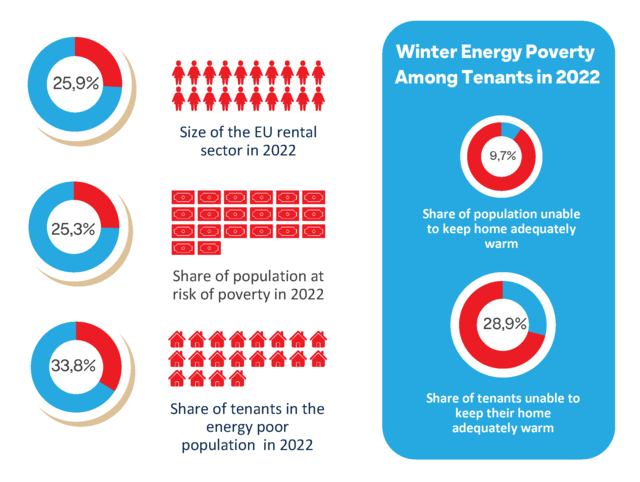

Landlords and tenants are the crucial stakeholders to address for successful design and implementation of energy efficiency policies: approximately 40 million people are affected by energy poverty in 2022. The size of the rental sector in the EU is 25,9%. Low-income, high-energy expenditure and low level of energy efficiency in housing are the cornerstones of energy poverty. This is confirmed by the fact that between 2012 and 2015, low-income households in Northern, Southern and Western Europe spent more on rent than the EU average, with a high share of low-income tenants who are overburdened by market rate rent spending 35% of their income on rent.

In the PRS, for which as many as 25,9% of EU citizens rely on for housing, access to affordable renewable energy and energy efficiency renovations as well as required accompanying regulatory changes are key to alleviating energy poverty. The ENPOR research found, that energy poverty is poorly understood in relation to the PRS and that in Europe, PRS tenants are more likely to be suffering from this condition than the general population. PRS housing is the least energy efficient and least well-maintained in Europe.

The PRS must be considered when designing energy efficiency policy measures on the national scale, with specific conditions to include when energy poor households are involved.

An EU wide definition of energy poverty is enshrined in the revised Energy Efficiency Directive (EU/2023/1791). The EU legal framework requires Member States to identify and tackle energy poverty in their National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs). ENPOR research found that currently 85% of the existing energy efficiency policies implemented since 2010 are not targeted at the rental sector. Only 28% of these policies were targeted at low-income groups and only 6 policies were aimed at tenants.

The long-term alleviation of the energy poverty should be achieved through the energy efficient renovation of buildings

Main Recommendations

- Energy efficiency in buildings coupled with strong communication and advisory measures should be considered as the structural solution to alleviate energy poverty: a process that intercepts human lives and stories.

- Both landlords and tenants are the crucial stakeholders to address, when it comes to successful design and implementation of energy efficiency and renovation of building policies.

- Energy poverty should be defined in national legislations, with a single definition adopted.

- All Member states should set up a framework that diagnoses energy poverty, as well as monitor their progress adjusting their existing policy framework and adding new measures.

- Increasing building energy efficiency in the private rental sector should be part of energy poverty alleviation strategies. Such strategies should support landlords with long term monetary incentive to invest in energy efficiency and protect energy poor tenants from disproportionate total rent increase and renoviction.

- Financial support should be always coupled with professional or technical advice, one-stop-shops and renovation campaigns in cooperation with municipalities as technical support.

- Linked to technical advice, it is key to fund training and information measures for social and health workers to identify and support vulnerable people at risk of energy poverty.

- Supportive and continuous framework for municipalities should be set up to implement relevant measures and provide long-term funding as well as monitoring gathering continuous data.

- Match energy advice (materials), outreach channels and messaging to the diverse realities of energy poor households in the PRS. Policies must be inclusive of all gender identities, accounting for gender differentiated needs of women and families, and be based on sex-disaggregated data that is systematically collected on a regular basis.

- Member States should put in place support and information measures on access to renewable energy and renewable energy communities that enable new business models or dedicated subsidies that target the energy poor.

- Establish policy measures in close collaboration with different stakeholders involved in the rental sector.

- Member states that have not transposed the EED 2018/2002, ED 2019/944 and RED 2018/2001 in national law yet, should do it urgently. All member states should consider enshrining in national law a public intervention model and set prices for the energy supply to energy poor households in crisis and oblige energy suppliers to provide adequate information on alternative measures to disconnection in advance.

Policy outcome fiches per country